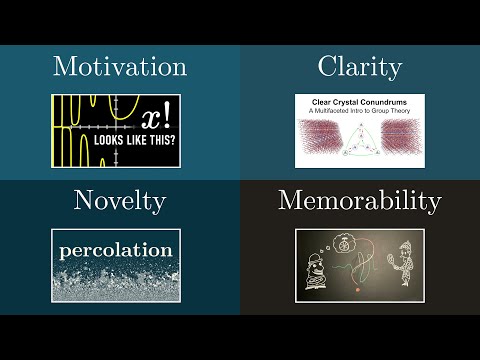

In the last month or two, there’s been a measurable increase in the attention to a wide variety of smaller math channels on YouTube. My friend James and I ran a second iteration of a contest that we did last year, the Summer of Math Exposition which invites people to put up lessons about math online. Could be a video, could be an article - any medium you dream up, whatever topic you dream up and we have some prizes available for the ones that we deem, in some sense best, whatever that could mean. The deadline for submissions was a little over a month ago and if we just focus on the video entries, they’ve collectively accumulated over 7 million views since that time. Considering that the vast majority of these are uploaded to very young channels where the video is often just the first or the second upload, this was really exciting for me to see. I suspect a big part of the reason for this rising tide is that after the submission deadline, we ran a peer review process where an algorithm would feed participants two different videos to compare and they’d be asked to vote which one of these is “better” according to a few criteria. Now, that process generated over 10,000 comparisons which, on the one hand helps to provide an initial rough rank ordering of all the videos but more important than that, any judgments or rankings, it gave an excuse for many hundreds of people to upload around a similar time and then collectively view each other’s work helping to jump start a cluster of videos with a shared viewer base. And that 7 million number doesn’t account for other videos on these channels, for instance the many submissions people made to last year’s contest which since this year’s deadline collectively jumped up by about 2 million views. One group who told me that last year’s contest was what inspired them to put up their first video mentioned to me that a video they had made in between the two contests managed to suddenly jump from 1000 to 600,000 views during the peer review process for this year’s contest. Despite not being among those videos reviewed. This is all to say, there can be a surprising value in the seemingly simple presence of a shared goal and a shared deadline. And again, these are just the video entries where it’s easy for us to run these analytics to quickly get a sense of the reach. Many of my favorite entries were the written ones. The spirit of the contest, as you can no doubt tell, is getting more people to put out math lessons and on that front, mission accomplished. But I did promise to select five winners - lessons that stood out as especially valuable for one reason or another and that brings us to this video here. To choose winners, James and I both spent a couple weeks giving a pretty thorough look at over 100 of the top entries as determined by the peer review process and we also recruited a few guest judges from the community to help look at a subset of these and make sure that our own biases and blind spots aren’t playing too heavy a role. Many, many things to them in the time they offered. I won’t tell you the final decision until the end of the video. What I thought might be more fun is to lead up to it by talking through the criteria that I had in mind when making this election, highlighting as many exemplary submissions as I can along the way. Hopefully giving any of you who are looking to put out your own math lessons online at some point a few concrete things to focus on. At a high level, the four criteria I told people I’d look out for were motivation, clarity, novelty and memorability. The first two are probably the most important and let’s start with motivation. This actually has two meanings I can think of - one on the macro scale and one on the micro scale. By macro scale motivation, I mean how well do you hook someone into the lesson as a whole. This video by Aleksandr Berdnikov opens by asking why it is that when you hear a plane approaching, the pitch of its sound seems to slowly fall. He points out how a lot of people assumed this is the Doppler Effect, but that this doesn’t actually hold up to scrutiny since for example, that pitch actually rises as the plane is going away from you. It’s a good point and an interesting question, you have my attention.

One of my favorite articles in the batch by Adi Mittal prompts you to wonder about an algorithm behind the panorama feature on your phone and proceeds to explain one - why that’s not trivial and then two, the linear algebra and projective geometry involved in a DIY style project to stitch together two overlapping images taken a different angles. Application and tangible problems can make for great motivation, but that’s not the only source of motivation. Depending on the target audience, a good nerd sniping question can also do the trick.

This video on the channel Going Null opens with a seemingly impossible puzzle. Ten prisoners are each given a hat chosen arbitrarily from ten total hat types available. It is possible for some of the prisoners to have the same hat type as others and everyone can see all of the other hats but not their own. After given a little time to look everyone else’s hat and think about it all, the prisoners are to simultaneously shout out a guest for their own hat type. The question is, can you find a method that guarantees at least one of the prisoners will make a correct guess?

This video by Eric Rowland motivates the idea of p-adic numbers than the p-adic metric by showing how if you take 2^10th and 2^100th, 2^1000th, so on and so on and you assign distinct colors to each digit lining them all up on the right. You can see that their final digits line up more and more with larger powers. Then he asks the question of whether it’s reasonable to interpret this as a kind of convergence, despite the fact that these numbers are clearly diverging to infinity in the usual sense.

A completely different form of motivation can come from showing the historical significance of a problem or field in a sense giving the viewer a feeling that they are part of something bigger. One excellent video on a channel A Well-Rested Dog provides an overview of the history of calculus and the progression of how some of the world’s smartest minds grappled with the nuances of infinity and infinitesimals. It’s the right mixture of entertaining and detailed and he goes on to talk about how learning all of this made his own questions and confusions in a calculus class feel validated, which I think a lot of students can resonate with.

This example is less about the intro of a video motivating the lesson it teaches and more about the entire video motivating an entire field. And another one like that would be this lecture by the channel Thricery, laying out how Cantor’s diagonalization argument and the Halting Problem and a number of other paradoxes people might have heard of in math, computer science and logic all actually follow the same basic pattern and moreover, if you try to formalize the exact sense in which they follow the same pattern, that ends up serving as a pretty nice motivation for the subject of Category Theory.

And the last flavour of motivation I’ll mention is if you can somehow make the learner feel like they’re playing an active role in the lesson. This is very hard to do with a video, maybe even impossible, and it’s best suited for in-person lessons but one written entry that I thought did this especially well was an inverse turing test, where you as the reader are challenged to come up with a sequence of ones and zeros that appears random and the article goes on to explain various statistical tests that you could apply to prove that the sequence was actually human generated and not really random. The content of the article is centered around the particular sequence that you, the reader created and you’re invited to change it along the way to try to get it to pass more tests. It’s a nice touch and I could easily see this working really well as a classroom activity. No matter what approach you take or what motivation you prefer, it is essential to give viewers a reason to care. This is true for all kinds of content, but it is especially true for educational content, and even more so for math, which often requires a lot of concentration and thought. One of my favorite podcast authors articulated this best on their website with a manifesto called “The Axioms of Learning”, the first of which states: “In a perfect world, students pursue learning not because it is prescribed to them but rather out of a genuine desire to figure things out.”

I think I have made the mistake of over-philosophizing in my video introductions in the past. Motivation is key, but it doesn’t have to be long-winded. Often, what keeps the viewer engaged is to get right to the point and leave any commentary about bigger themes and connections to the end. It’s best to motivate using clear examples, rather than grand statements or promises of what is to come.

By “micro-scale motivation”, I mean that each new idea introduced in the lesson should make sense to the learner. For example, in this video by Joshua Maros about Ray Tracing, he outlines the main idea and intuition for each topic before introducing any technical aspects. This makes it so that when the equation or algorithm is described, it doesn’t feel like it is being presented out of the blue.

Similarly, this video by Michael DiFranco about extending the factorial function does a great job of motivating each step. He starts by observing the properties that are true of the normal factorial function, and uses those desired properties to motivate various alternate expressions and ultimately a satisfying answer.

One template for micro-scale motivation when introducing a complex solution to a problem is to start with a naive but flawed solution and then refine it. This article by Max Slater on differential programming does this well. He starts by describing the most obvious approach and then what flaws it has, and uses that as motivation for another approach. But that one has its own flaws, and fixing those motivates yet another approach, and so on. The ideas he builds up to, dual numbers and backward mode automatic differentiation, could feel confusing if presented out of the blue. But in context, having motivated each new idea by pointing out flaws with the previous ones, it all makes sense. Turning back to that same prisoner hat puzzle I referenced earlier, one of the other things I liked about it is how the author doesn’t just present the solution. There are plenty of puzzle videos out there which do that. Instead, he gives a pretty authentic look at the wrong turns and tangents that are involved in the problem solving process, not even eating up too much time to do so, and he justifies each new step with a general problem solving principle. All of this micro scale motivation could just as well be categorized as a subset of clarity. If motivating a lesson determines how much attention and focus the viewer is willing to give you, clarity determines how quickly you burn through that focus. The best hook in the world is wasted if the lesson which follows is confusing.

This presentation by Ex Planaria talks about how to describe various crystal structures using group theory, which considering the complex 3D forms involved and the fact that most people don’t know Group Theory, has the potential to be very confusing. But they do a really effective job at keeping concrete examples front and centre guiding the reader to focus on one relevant pattern at a time and distilling down to a simple version of an idea before seeing how that fits into a broader more general setting. In general, entries that struck me is especially clear would often keep one or two examples front and center and that often give a feeling of playing with those examples - may be running simulations or tweaking them to run up against edge cases and all around giving the viewer a chance to build their own intuitions before general rules are presented. The example doesn’t even have to be explicit. In a visually driven lesson, the choice of what to show on screen when making general points is often a great opportunity to offer the viewer a concrete example to hold on but without wasting too much time explicitly talking about that example or over emphasizing its importance. This I think is part of what gives visually driven lessons the opportunity to be clearer.

As a brief side comment by the way loosely related to clarity - for any of you who want to use music in the videos, while music can enrich the story telling aspect of a lesson - setting the desired tone and the momentum, once you’re getting into the meat of a technical explanation, it’s very easy for the music to do more harm than good. If it’s there at all, you want it to be decidedly in the background and not calling attention to itself. I recognize some hypocrisy here, it’s definitely something I know I’ve messed up with past videos and it’s just worth thinking about whatever benefit you see from the music. You don’t want to incur a needless cost on clarity that outweighs that benefit.

Moving on to novelty, this is another category that has two distinct interpretations. One would be stylistic originality. Back when I created this channel, part of the reason I wrote my own animation tool behind it was to ensure a kind of stylistic originality. Well, the main reason was it was a fun side project and having my hands deep into the guts of some tool helped me to feel less constrained in trying to visualize whatever came to mind. But being a forcing function for originality was at least a small part of my reasoning. This means there’s at least a little hint of irony in the fact that if we fast forward to today, so many of the entries in this contest used that tool (Manim) to illustrate their lessons. I have nothing wrong with that. It actually delights me. It’s why I made it open so and I’m very grateful to the Manim community for everything they’ve done to make the tool more accessible. But I would still encourage people to find their own unique voice and aesthetic whatever tools they use and whoever they take inspiration from. I don’t want to over emphasize that point because it’s the much less important half of novelty. The much more important kind of novelty is when the thing you present would have been very hard to find elsewhere on the internet. This could be because it is a highly unique topic or because it is a very unique perspective. For example, the video on percolation showed a completely fascinating toy model for studying phase changes, a model where it is easier to make exact proofs. The level of depth and clarity provided makes it fair to say that you wouldn’t find something like this on YouTube if this group hadn’t made it.

As to memorability, lessons take off when they ask a question that’s just so fun to think about or provide such a satisfying aha moment that it stays with you long after watching it or reading it. This is highly personal and subjective. To my taste, this video by Daria Ivanova discusses the question of when it’s possible for a single track to have been left by a bicycle, which is just so fun to think about. This video by Gergely Bencsik about how involute gears work had a really satisfying way of explaining why a certain gear design pattern works so well that for me at least just stuck.

So, who are the chosen winners? In the announcement, I promised that one winner slot would go to an entry that was made as a collaboration and that one goes to the percolation video. The other four winners are, perhaps unsurprisingly, also ones that I’ve already mentioned. They include the post about describing crystal structures with group theory, the video covering the history of calculus, the one about ray tracing and the algorithms to make it faster and the problem solving lesson centered around the tricky hat riddle.

These entries really do speak for themselves. So, rather than telling you too much more here, I encourage to check them out. To be honest, after I got it down to about 25 entries that I wanted to at least be honorable mentions, it was exceedingly hard to actually choose winners from that. Since for each of these, I could easily envision a target audience for whom that entry would actually be the best recommendation. It was a game of comparing apples to oranges but times twenty-five.

Below the video, I’ve left links to the other 20 that I chose as honorable mentions and to a playlist that contains all the video submissions and also to a blog post containing links to all of the non-video submissions. Thanks to a sponsorship from Brilliant, each winner will get a thousand dollars as a cash prize and also - and much more importantly I think - a rare addition golden pie creature. Also, after the initial announcement, Risk Zero and Google Fonts both generously reached out offering additional prize sponsorships. I’d also like to thank Protocol Labs for another contribution to help us cover the cost of managing the whole event.

Thanks to everybody who participated and to everybody who helped in creating this rising tide for new math channels and new math blogs that we’ve seen in the last month. It was genuinely inspiring to see just how well this all went.