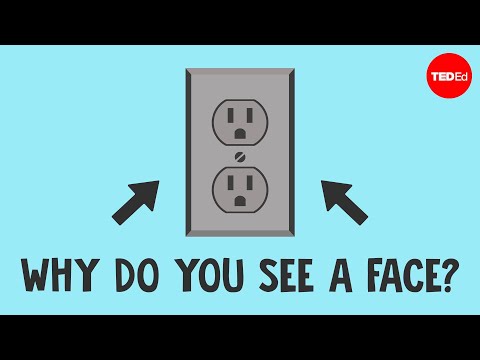

Imagine opening a bag of chips only to find Santa Claus looking back at you, or turning the corner to see a smile as wide as a building. Humans see faces in all kinds of mundane objects, but these faces aren’t real— they’re illusions due to a phenomenon known as face pareidolia. So why exactly does this happen, and how far can this distortion of reality go?

Humans are social animals, and reading faces is an important part of our ability to understand each other. Even a glimpse of someone’s face can help you determine if you’ve met them before, what mood they’re in, and if they’re paying attention to you. We even use facial features to make snap-judgments about a person’s potential trustworthiness or aggression. To capture all this vital information, humans have evolved to be very sensitive to face-like structures. Whenever we see something, our brain immediately starts working to identify the new visual stimuli based on our expectations and prior knowledge. And since faces are so important, humans have evolved several regions of the brain that enable us to identify them faster than other visual stimuli. Whereas recognizing most objects takes our brain around a quarter of a second, we can detect a face in just a tenth of a second. It makes sense that we’d prioritize identifying faces over everything else.

But brain imaging studies have revealed that regions may actually be too sensitive, leading them to find faces where they don’t exist. In one study, participants reported seeing illusory faces in over 35% of pure-noise images shown to them, despite the fact that nothing was there. It might seem concerning that our brains can be so wrong so often, but these illusory faces might actually be a byproduct of something evolutionarily advantageous.

Since processing all the visual input we encounter quickly and correctly is an enormous computational effort for the brain, this kind of hypersensitivity might act as a useful shortcut. After all, seeing illusory faces is usually harmless, while missing a real face can lead to serious issues. But for hypersensitivity to be more helpful than harmful, our brains also need to be quick at determining when a face is real and when it isn’t.

So how fast can our brains tell when they’ve been duped? To answer this question, researchers used a form of brain imaging known as magnetoencephalography. By measuring the magnetic fields caused by electric currents in the brain, this technique allows us to track changes in brain activity at the scale of milliseconds. With this tool, researchers revealed that the brain generally recognizes a face as illusory within a quarter of a second— around the same time that we can identify most non-face visual stimuli.

However, even after our brain knows the face is fake, we can still see it in the object. And by messing with these brain areas, we can further impact our ability to differentiate between fact from fiction. In one study, researchers stimulated a participant’s fusiform face area while they were looking at a non-face object. As a result, the participant reported momentarily seeing facial features despite the object remaining unchanged. And while looking at a real face, stimulation of this same area created perceived distortions of the eyes and nose.

These studies suggest that certain features are crucial to face detection. Just three dots can be enough to represent eyes and a mouth. People will even assign gender, age, and emotion to illusory faces. It’s unclear whether a person’s culture or individual history impacts these perceptions, but we do know that pareidolia isn’t unique to the human experience. Rhesus macaque monkeys show eye movements similar to our own when observing pareidolia-inducing objects and real faces, suggesting that this phenomenon is baked deep into our social primate brains.

So, next time you see an unexpected face in a coffee, car, or cabinet, remember that it’s just your brain working overtime not to miss the faces that really matter.