I was rejected.

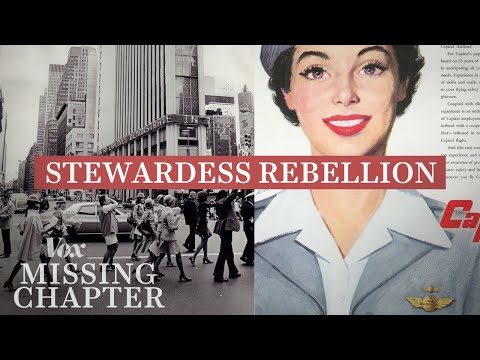

In 1971, National Airlines released an advertisement featuring a flight attendant and a new slogan: “Fly Me”. The campaign quickly included Jo, Denise, and Laura, and essentially tried to sell the stewardesses as sex objects. This campaign was successful, as ticket sales increased by 19%, and other airlines followed suit. This was one of the many ways the airline industry degraded and discriminated against flight attendants, until they stood together and pushed back. This fight was led by black women like Patricia Banks, who in 1960 became the first black flight attendant on a commercial aircraft. Airlines had incredibly strict hiring practices, such as age limits and requiring attendants to be single, white, healthy, and of a certain height and weight. These restrictions were designed to make the job feel exclusive, and the attractiveness of the job was used to sell an elite, glamorous image of air travel. Patricia’s story highlights the discrimination and unfairness that flight attendants faced for decades, and how they paved the way for working women in the US today. Patricia never heard back from Capital Airlines, while others did. It was a difficult experience for her, and she felt like something was wrong. Eventually, a chief stewardess saw her and told her that the airlines did not hire African Americans. This prompted Patricia to file a case with the New York State Commission Against Discrimination to investigate Capital Airlines for racist hiring practices. During the process, Patricia faced threats of being raped and murdered, and had to involve the police. Despite the difficulty, she felt it was something she had to do.

The commission decided that the airline had discriminated against Patricia by maintaining a policy that barred black applicants from employment. In 1960, Capital was ordered to reverse that policy and hire Patricia, making her one of the first black commercial flight attendants.

A few years later, the Civil Rights Act became federal law, prohibiting employment discrimination on the basis of race and sex under Title VII of the act. This gave black women the opportunity to challenge airlines for the racism they experienced in the industry, and one by one, they secured their right to fly. By 1965, there were 50 black stewardesses working at 7 of the largest US carriers.

The same legislation that put an end to racist practices was also used by stewardesses to put an end to sexist policies at work. Betty Green Bateman, who was fired after Braniff Airlines discovered she had been secretly married for more than a year, launched a challenge against the airline. After months of fighting with the airline, she was allowed to keep her job, which forced multiple airlines to overturn their marriage rules.

However, airlines leaned into the sexy stewardess stereotype to make money, debuting new ads and uniforms that contradicted what the stewardesses were fighting for. With the Women’s Liberation Movement, there was so much pressure and encouragement among the women to challenge this injustice. Eventually, the airlines had to back down, and the Women’s Liberation Movement was a turning point for stewardesses all around. We’ve got to do something. And that’s exactly what stewardesses did. They started some of the first independent, women-led unions in US history, and formed groups like Stewardesses for Women’s Rights to tackle age restrictions, marriage policies, uniforms, and weight limits. Though the mainstream movement was largely focused on white women, black stewardesses were fighting against racist appearance standards in the industry, too. For example, one United stewardess who was fired for wearing her hair in an Afro successfully sued and forced the airline to apply its regulations equally without regard to race. Other policies took decades to overturn, such as regulations that grounded attendants when they became pregnant or weight restrictions, which took a 17 year legal battle against American Airlines to undo.

As restrictions changed, the makeup of the industry changed as well. Older, married, and black stewardesses were increasingly joining the profession. The legal fights had altered the airline industry, and taken together, they would also alter the future of women’s labor in the US. The rights that these women won have become case law about sex discrimination in employment, and have been used in gender discrimination cases and some LGBTQ cases. This all built on the efforts of stewardesses in the 1960s and 70s, which still have an effect today.

It’s estimated that up to 30% of stewardesses were secretly married when no-marriage policies were rampant in the airline industry - just another one of the many ways they challenged sex discrimination at work. We pick stories like this for Missing Chapter because it’s important to talk about underreported history, and to keep this work free for everyone. If you’d like to help support this work, consider becoming a Vox contributor. You’ll get exclusive behind-the-scenes access to emails, updates, and other ways to get involved in our work. To join our mission of keeping high-quality information free for everyone, visit Vox.com/givenow.