I’ve been noticing something lately when I’m sitting in traffic: either I can’t see past the cars in front of me, or the cars around me are towering over me. It turns out there’s a big reason for this: the production of passenger cars like sedans and wagons for sale in the US has been in freefall since 1975, and in their place has been the steady growth in the production of SUVs and trucks. Last year, SUVs and trucks made up 80% of all new car sales, compared to 52% in 2011.

The fact that Americans like big cars probably won’t shock anyone; they are everywhere, even in my parking-scarce neighborhood in Brooklyn. But the reasons behind this transformation are more than just cultural; they go back to a 50-year-old policy that kicked off a huge shift in the way US cars are designed.

Alaska was the first state to go big-car dominant in 1988, and New York was the 45th state to succumb to the takeover in 2014, according to a Washington Post analysis. So I’m wondering if you have any advice for things they should look out for on the road. Anywhere you stop, count the number of SUVs versus the number of passenger cars.

In the Costco parking lot, I counted eleven SUVs in a row - a new record! Once you learn about how much big cars dominate the road, it’s like you can’t unsee it. People have lots of reasons for choosing a big car, and certainly the infrastructure in the US supports that choice. Unlike a lot of other countries, our built environment revolves around cars - we have wide roads and wide, plentiful parking spaces and homes with plenty of parking.

Fuel is also extremely cheap in the US due to low taxes on gas, which is another deterrent for big cars in other countries. But there’s another overlooked bias towards big cars related to why SUVs exist in the first place. In the 1970s, there was a shortage of foreign oil in the US, so the US government set rules for automakers to start making cars more fuel efficient to lessen our dependence on the global oil market.

By 1985, new cars had to get 27.5 miles per gallon or roughly double their fuel efficiency. These new rules applied to cars like sedans and station wagons, but there were types of vehicles the US government exempted from these rules, like pickup trucks. The idea was if these are working vehicles used by farmers, construction crews, and companies hauling freight, then those vehicles need to be able to do their job without being held to unrealistic fuel economy standards.

So passenger cars got one set of strict rules, and this other category called light trucks got another set of more relaxed standards. This regulation created an incentive for carmakers to transform light trucks into a vehicle for everyday use. Put in a radio, lots of cargo space, and comfy seats, and voila - that’s how we got the SUV. OK, girls, we’re off in our new Jeep Cherokee. Behind its classic look, it’s tough and powerful. Automakers don’t need to invest as much in fuel economy and emissions improvements when producing and selling SUVs, as they fall under a category that is less strictly regulated. The Wagoneer was low-volume, bespoke, and expensive, so few people bought it. People living in Manhattan would take the SUV to the Hamptons or upstate New York for skiing, which is how the SUV first came to be.

Ralph Gilles, head of design at Stellantis, a conglomerate of car companies that includes Jeep, explains that one of the first SUVs was the Chevy Blazer, which was built on the frame of a Chevy S-10 truck. This is the traditional definition of an SUV, and to meet the legal definition of a light truck it had to have specific clearance angles and dimensions. This is when the utilitarian vehicle was transformed into a luxurious one that was still practical.

The Jeep Grand Cherokee was built like a passenger car, in one piece or unibody. This is the separation between traditional SUVs and the new, popular crossover category. Crossovers are more efficiently packaged and don’t have a frame. The Grand Cherokee was part of the success story of SUVs in the ’90s and 2000s, which continues today.

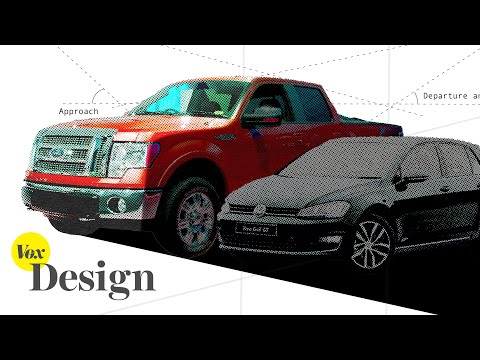

This bias towards light trucks is why a company like Volkswagen, which once sold primarily passenger cars, has discontinued a lot of them in favor of SUVs and crossovers, and even stopped producing their wagons, including the Jetta Wagon. Ford has also stopped producing all of their passenger cars except for the iconic Mustang.

At this car dealership, it was revealed that Buick used to be mostly sedans, but now they only sell crossovers. The last time they had a Buick passenger car was three or four years ago, and they had 1 to 100 SUVs on the lot. The market has shifted and now they don’t even produce a Buick sedan.

The chart now makes more sense, as 1975 was the year the fuel economy standards for sedans and wagons were passed, the same ones that didn’t apply as strictly to SUVs and trucks. Automakers have been marketing SUVs more preferentially than passenger cars, and have developed more models that fit into the SUV category, making it easier for people to get into an SUV than a passenger car.

As of 2016, the fuel economy standards have changed, with vehicles still separated by the stricter standard for passenger cars and the looser standard for light trucks. However, within those categories, there are more breakdowns. The larger cars within each category get weaker rules, meaning automakers are not only incentivized to phase out passenger cars in their fleet, but also to make each category bigger.

The Toyota Camry and Toyota RAV4 have both become longer and wider, and Rhode Island is the very last state in the country to go light truck dominant. We have started the transition to electric vehicles, but they are still larger, heavier, and taller, making them less energy efficient. Whether it’s an electric car or an internal combustion powered car, one sobering impact of big cars is the threat it poses to pedestrians. One study found that replacing the growth in SUVs with cars would have averted over a thousand pedestrian deaths, as people on foot get hit higher and in more vulnerable regions when hit by an SUV or a truck rather than a passenger car.

Before hitting the beach, I stopped at my friend Kevin Wright’s house. He’s bucked the SUV trend and drives a Honda Fit, a car that was discontinued in 2020. We had our daughter about 17 months ago and were thinking about the second car, but ultimately decided to kind of go the other direction and got an e-bike, as it gets good gas mileage and we wanted to minimize our carbon footprint as much as we can.

Even though we’re in Rhode Island which was the last holdout for SUV dominance, there are still a lot of SUVs here. I’m curious if you think there’s any political will or urgency to change this trend towards bigger cars, as it has environmental, economic, and safety concerns. There is a desire among the younger people and more politically active people to try to make it so that an SUV is not the default vehicle choice for American families.

The US is unlikely to become a small car country any time soon. But this dramatic transition to big cars wasn’t just about consumer choice; it was enabled by a policy choice. So if we want our roads to look different, we can try and start there.